Welcome to the fifth section of our exploration of the elements of the Inca altar at Qoricancha! A representation of the Andean cosmovision.

It shows us the hierarchies of the Inca criteria; moreover, it explores the reasons for correspondence and equality, presenting a symbol that is still being studied.

If you haven’t seen Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 or Part 4 yet, we remind you to read them first and then come back here.

Symbols Description

Ñawi

The next symbol is the eyes.

“Ymaymana Ñauraycuna” represents the inhabitants of the inner world or “Ukhu Pacha.”

In this realm, inhabited by spirits of darkness, the dominant figure is “supay” or demon, a bloodthirsty and murderous being who tempts humans to disrespect the supreme creator.

Supay is accompanied by other infernal demons such as “Ccañajhuay,” “Ñaqac,” “Saqra,” “muqui,” “Achaq’alla,” “Yscay Uya,” “Ñaupa Runa,” and “socca.”

Alongside these malevolent beings, other spirits reside here, confined to these places due to the harm they have caused to humans or nature.

“Inca” Ccari

The following drawing represents a man.

Entrusted with the task of the future, he is the privileged being of creation. He possesses energy and vitality, along with the gift of knowledge, love, and wisdom. He holds the messages of the past and must find his spirituality.

Man is responsible for discovering methods for social coexistence, seeking the development of work techniques, and creating a harmonious society among all living beings, in harmony with nature and in close connection with the entire universe.

During the time of the Incas, man held more than any other being in the world, knowledge inherited from prehistoric times.

His expertise in natural and folkloric medicine, his grasp of natural selection, and his command of hydraulics and land treatment, especially his philosophy and metaphysics, rendered him a privileged being and earned him recognition as a divine creation.

“Inca” Warmi

The following drawing corresponds to that of a woman. The woman shares all knowledge with the man.

There was no inequality or gender dominance among the Incas.

However, within harmony and correspondence, women performed much more diverse roles than men.

Almost all tasks, including warfare, were also carried out by women.

Like men, women also knew how to spin and weave.

The only task inherently associated with the female gender was domestic service.

This egalitarian and natural treatment fostered a harmonious society during the time of the Incas, but the intrusive attitude of a Western society, which neither feared nor respected the supreme values of humanity, disrupted it.

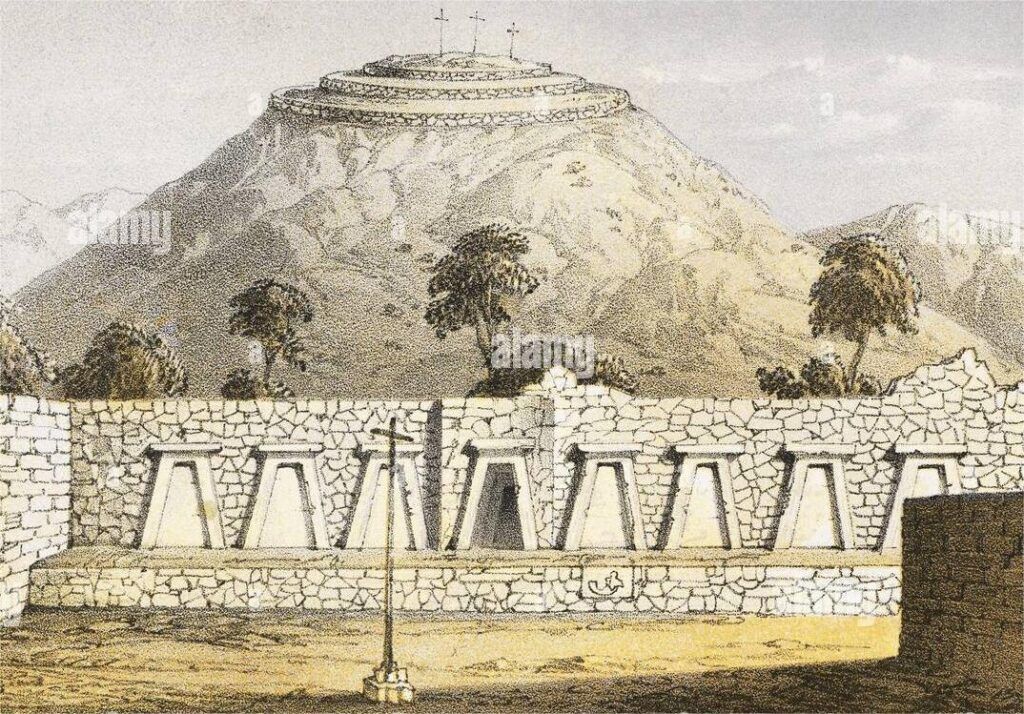

Tambo

The lower drawing of the cosmogonic retable is the Collca, which means granary, storage, or depot. It is also known by the name Tambo.

The Andeans covered this drawing on the altar of Qoricancha with plates of gold and silver, reflecting the importance they attributed to storage.

Storing is part of a philosophy of life.

The food, clothing, tools, decorations, weapons, gifts, and everything that filled the Inca Collcas were instruments for interacting with other communities.

During the Inca period, there were numerous towns on the coast, in the jungle, and in the highlands that had not yet emerged from prehistory.

Educating those peoples and integrating them into Inca civilization was the greatest achievement in the entire history of the Tahuantinsuyo. The Collcas were filled with food, so diverse that we can only recognize about 10% of it.

Here is a list from Felipe Guaman Poma: “They had provisions of food in this way: potatoes, tubers, oca, mashua, radish, quinoa, tarhui, chuño, caui, caya, tamos, llama, vicuña, alpaca, paco, guanaco, taruca, partridge, chichi, ants, mosquitoes, mushrooms, lakes, ducks, herbs, llachoc, onquena, ocoroto, eacacha, mauca, amaca, suya, squash, thousands of fruits, peppers, uchu, rocoto, and other small items.”

- Candia M, C; Del Solar, M y Iwaki O, R. (1994). Altar Inka del Ccorik’ancha. Cuadernos Andinos Nº10.

- Estermann, J. (1998) Filosofía Andina. Un estudio intercultural de la sabiduría autóctona andina. Biblioteca Seminario San Antonio Abad, Cusco.