In the highlands of Peru, there exists a festival that is both shocking and profound—an intense expression of colonial memory, indigenous resistance, and cosmic symbolism. In the Yawar Fiesta, or “Blood Festival,” participants ceremonially tie a condor—a sacred Andean bird—to the back of a Spanish bull, creating more than a spectacle: a ritual performance rich with symbolism. Their battle enacts the history, pain, and spiritual tension between two worlds.

What Does Yawar Fiesta Mean?

The name Yawar Fiesta comes from Quechua and Spanish:

- Yawar means blood in Quechua,

- Fiesta is festival in Spanish.

Thus, Yawar Fiesta is the Festival of Blood, but the term encompasses far more than violence. It is a symbolic reenactment of the colonial struggle, and a form of ritual reconciliation between the Andean world and the colonial legacy (Arguedas, 1941).

Where Is Yawar Fiesta Celebrated?

The most famous Yawar Fiesta takes place in Cotabambas, in the Apurímac region of southern Peru, but versions exist across other Andean provinces. Communities typically hold the festival during Independence Day week (around July 28), but its roots predate the Republic and draw from Inkan ritual battles and agricultural festivals.

Remote communities still speak Quechua and keep Pachamama, Apus, and ancestral spirits central to everyday life.

The Condor and the Bull: Symbols of Yawar Fiesta

The community stages the dramatic event at the heart of the Yawar Fiesta by tying a live condor—the sacred bird of the Andes—to the back of a Spanish bull, a colonial symbol.

The condor (Kuntur) represents freedom, spiritual vision, and the Andean people. It is associated with Hanaq Pacha (the upper world) and is believed to carry messages to the gods.

The bull represents Spain, colonial violence, and imposed order. As a foreign animal brought by the conquistadores, it embodies brute force, oppression, and the trauma of invasion (Flores Galindo, 1988)

The community enacts the fight between these two beings not as a mindless act of cruelty, but as a ritualized struggle filled with spiritual and historical meaning.

Structure of the Celebration

The Yawar Fiesta is a multi-day event involving music, dances, offerings, and community participation. Each phase carries its own symbolism:

- Calling the Condor: Community members travel to high peaks to capture a condor, often offering it food and coca. It is believed that the condor volunteers spiritually, linking the animal to Andean ritual sacrifice.

- Dressing the Bull: The bull is decorated with red cloth, alcohol, and sometimes firecrackers. It becomes a living altar, representing the forces of colonization.

- The Ritual Battle: The condor is tied to the bull, and the two are released in the arena. The condor strikes with its claws and beak, while the bull bucks and runs. Blood may be shed, but neither animal is killed intentionally—afterward, the condor is released, and its flight is seen as a sign of blessing or bad omen (Isbell, 1978).

This ritual echoes ancient tinku, a traditional Andean practice where opposing communities would ritually clash to release energy and fertilize the earth with blood.

Controversy and Resistance

Animal rights groups have criticized the Yawar Fiesta, viewing it as cruelty, and some regional authorities have even banned it. However, many Quechua communities actively defend the tradition, claiming that outsiders misunderstand its symbolism and spiritual depth.

For them, this is not about entertainment, but a cosmic drama, a way to heal collective trauma and affirm identity in a world that has tried to erase their culture.

Literature and Legacy

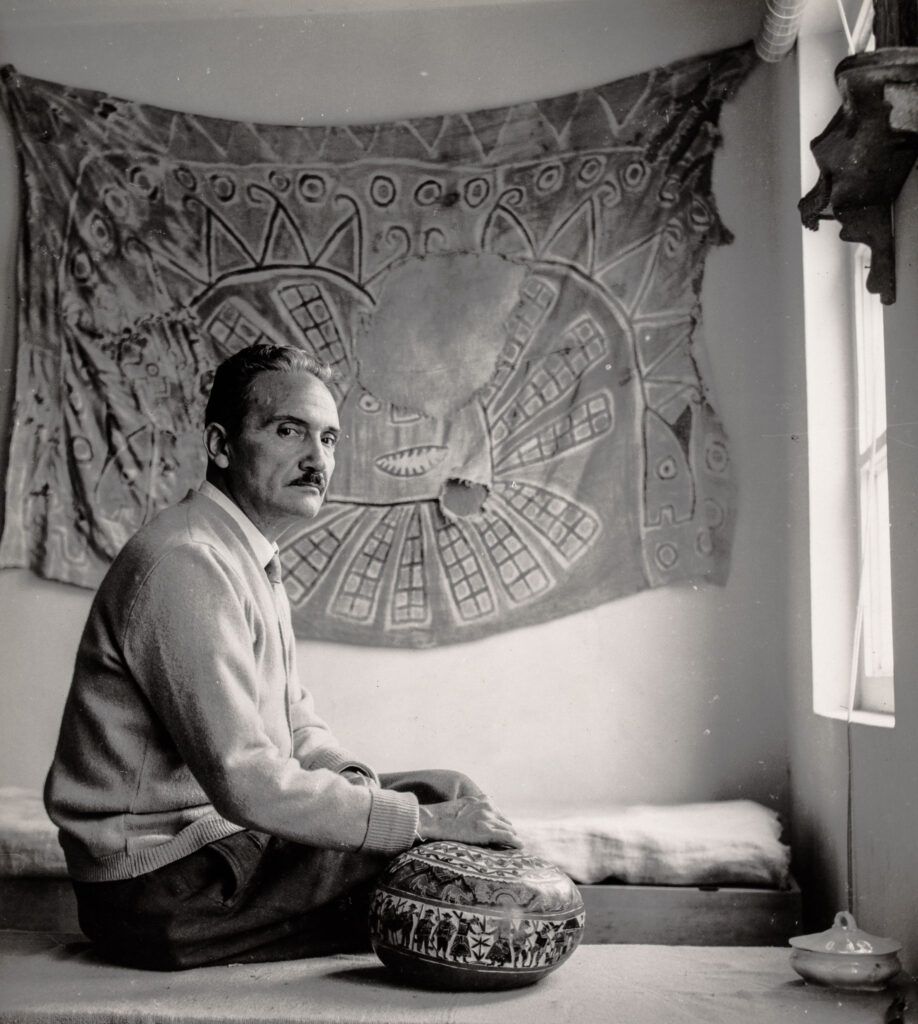

Peruvian writer José María Arguedas, who grew up in the Andes and spoke Quechua fluently, immortalized the Yawar Fiesta in his 1941 novel Yawar Fiesta. Through this story, Arguedas portrayed the cultural clash, the resilience of indigenous identity, and the deep ritual meaning hidden behind what outsiders might see as brutality (Arguedas, 1941).

Thanks to works like this, and to the ongoing efforts of Andean communities, the Yawar Fiesta continues not just as a performance, but as a ritual memory—a blood offering to history, to the land, and to the spirit of a people who never stopped flying.

Bibliography

- Arguedas, J. M. (1941). Yawar Fiesta. Editorial Losada.

- Flores Galindo, A. (1988). Buscando un Inca: Identidad y utopía en los Andes. Instituto de Apoyo Agrario.

- Isbell, B. (1978). To Defend Ourselves: Ecology and Ritual in an Andean Village. University of Texas Press.

- Dean, C. (2010). A Culture of Stone: Inka Perspectives on Rock. Duke University Press.

- Matos Mar, R. (2002). El mundo ceremonial andino. Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú.