Evidence of human capacocha in ancient Andean societies dates back to early periods. Such evidence is found in human remains, as well as in reliefs, textiles, ceramic paintings, and sculptural vessels.

This is the second blog where we talk about the controversial meaning of sacrificies. Please check part 1 of this interesting documents.

Ceremony of Capacocha

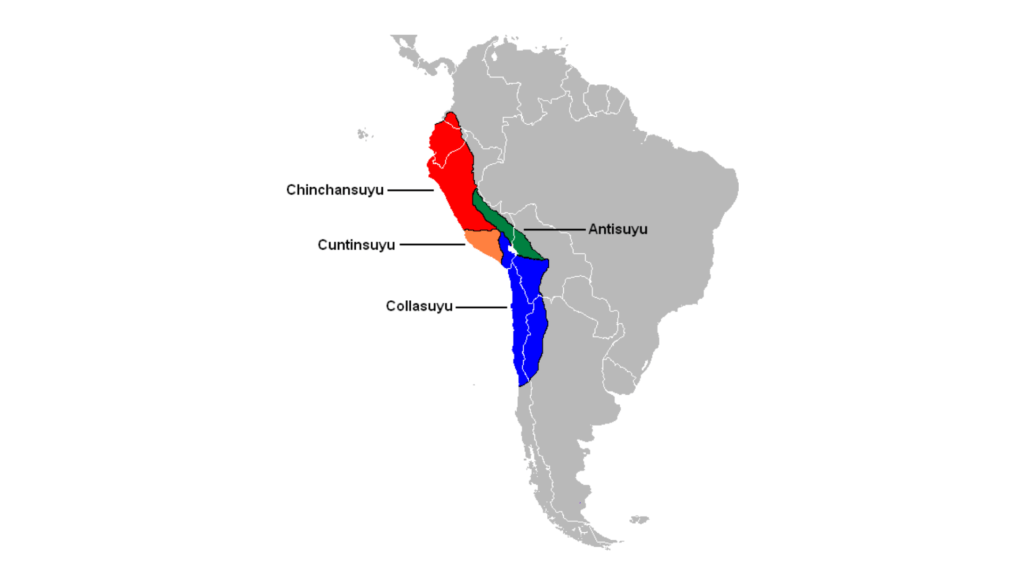

According to various documents, the individuals selected for their beauty and perfection, typically one or two from each town, came from the four regions of the Tahuantinsuyu:

Generally, they belonged to the upper class, meaning they were children of curacas or high-ranking individuals. The children would travel in procession from their places of origin to Cusco, accompanied by their relatives, local leaders, priests, and principal huacas, and bringing with them other offerings such as clothing and auquénidos.

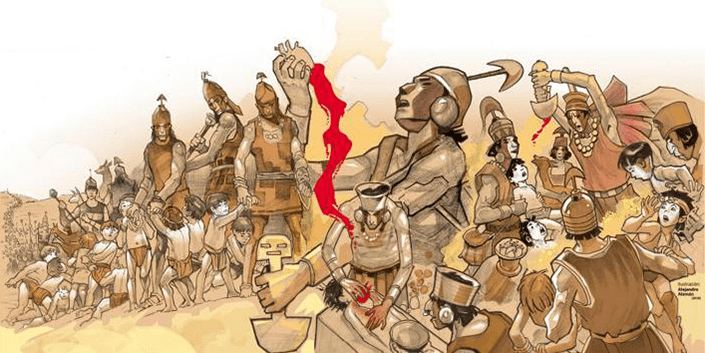

Upon reaching Cusco, they were settled in the Aucaypata plaza, where the Sapa Inca and his entourage would attend.

The children would circle the plaza twice in reverence to these deities, and the sovereign would touch them to impart his sacredness.

The Sapa Inca would also drink chicha with the Sun, asking it to accept these children into its service.

During the ceremony, people sacrificed a white llama and mixed its blood with corn to prepare yaguar sancu, the ritual bread distributed among the attendees. They also slaughtered a large number of auquénidos.

These children, along with others, would enter Cusco “almost immediately before the Inti Raymi festival,” which took place in June, during the major celebration for the Sun.

The ruler would speak to the Sun, asking it to accept the children for its service.

As part of the offerings to the huacas, people burned some sacrifices and prayed for the sovereign’s health, long life, military victories, and food abundance.

Documents indicate that they first gave the sacrificed individuals large amounts of chicha to sedate them before burying them or placing them in designated hollows. Some sources also mention drowning the victims.

At the end of the celebrations, the Sapa Inca distributed various objects among the processions. Their value and importance depending on the huaca involved.

Cusco had officials known as uilcacamayo, who were responsible for the administration and distribution of these objects in each suyu.

Reasons for Sacrifice

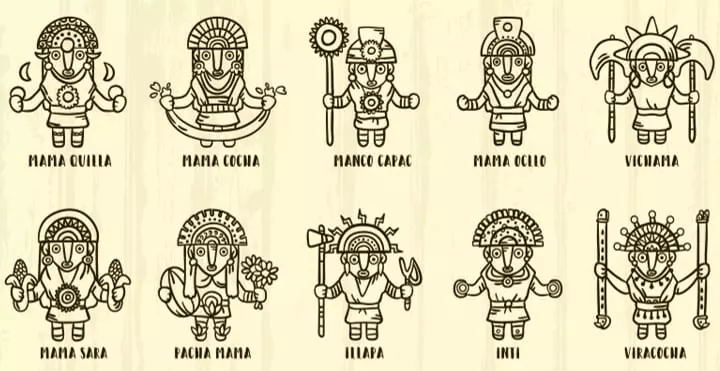

- Worship of Deities: The Incas sacrificed children and maidens to honor their main deities, such as Viracocha, Inti, and Illapa. The Sun received the most victims during the Capac Raymi in December and the Inti Raymi in June, which align with the solstices.

- Special Occasions: People performed sacrifices during wars, the ascension or death of the Sapa Inca, or when the sovereign fell ill. Rostworowski notes that these sacrifices aimed to ensure divine protection for the ruler and success in important endeavors.

- Sacrifices for the Sovereign’s Death: When a Sapa Inca died, people sacrificed many attendants, officials, wives, and maidens to accompany the ruler in the afterlife. Polo de Ondegardo and Acosta describe that, for instance, after Guayna Capac’s death, they sacrificed over a thousand individuals.

- Investiture Ceremonies: When a new sovereign ascended, people made sacrifices to ensure their health, longevity, and peace in their realm. Molina notes that only the most significant huacas received human sacrifices, while lesser huacas received auquénidos and valuable objects. Acosta and Ondegardo report that ceremonies involved the sacrifice of up to 200 children.

- War and Conquest Sacrifices: The ruler conducted sacrifices to ensure victory in military campaigns and to honor the Sun for success in newly conquered regions. Molina notes that these sacrifices included children selected for their beauty and health.

- System of Redistribution and Divine Access: Sacrifices also served as a means to integrate into the Tahuantinsuyu’s redistribution system. The sovereign was the supreme authority with exclusive access to deities and control over sacred distribution.