In the Andean world, agriculture was never merely about production—it was a sacred dialogue with Pachamama (Mother Earth) and the living energy known as Kawsay.

Every seed, every drop of water, and every terrace carved into the mountain reflected the principle of ayni, or sacred reciprocity: a living exchange between humans, nature, and the Apus.

The Inca civilization developed one of the most sophisticated agricultural systems in the world. Yet its genius was not only technical—it was spiritual.

The Incas saw the Earth as a being who breathes, feels, and responds. To plant a seed was to enter a covenant, an act of service rooted in Munay, Llankay, and Yachay.

Living in Harmony with the Land and Agriculture

Recent studies confirm that the Incas integrated sustainable ecological principles that remain relevant today.

They constructed terraces, practiced agroforestry, and managed mountain watersheds with precision, avoiding deforestation and erosion while maintaining soil fertility through the use of llama manure (Frogley et al., 2025).

Such systems demonstrate that Inca agriculture was as much about spiritual alignment as environmental balance.

At the heart of this relationship was water.

The sacred site of Tipón, near Cusco, reveals a stunning example of hydraulic engineering intertwined with ritual practice. Spring waters flowed through channels and fountains where offerings were made, symbolizing the continuous nourishment between humans and the divine (Bray, 2017; MDPI Archaeologies, 2023).

In Andean thought, Yaku Mama (Mother Water) was both a practical and spiritual force—the mirror of life itself.

Sacred Techniques of Inca Agriculture

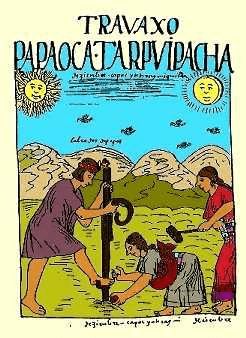

What we call “farming techniques” were, for the Incas, ritual technologies of energy exchange. Each act of cultivation was imbued with intention, offering, and reciprocity.

Some of the most revered techniques include:

- Wachu – the raised field system that allowed the land to breathe, creating warmth and protecting crops from frost. These fields mirrored the lungs of Pachamama, circulating life energy through the soil.

- T’oqo – ritual holes dug before sowing, symbolizing the womb of the Earth where Kawsay gestates. Offerings of coca, chicha, and llama fat were placed inside to awaken the spirit of fertility.

- Chakra Pampa – the communal field, where families gathered to sow and harvest together under the principle of ayni. Labor was ceremony; songs, dances, and prayers harmonized collective intention.

- Coca K’intu – three sacred coca leaves offered to the Apus and Pachamama before planting, aligning human effort with the consciousness of the mountain and the sky.

- Pachamamaq Challay – the “feeding of Mother Earth,” performed before each planting season to honor the soil and ask permission to awaken her abundance.

These techniques were not simply efficient—they were energetic and ethical. The Inca farmer was a ritual technician, one who cultivated both matter and spirit. The act of farming became a form of prayer, uniting cosmos and soil through human hands.

References

- Bray, T. L. (2017). Water, Ritual, and Power in the Inca Empire. Latin American Antiquity. Cambridge University Press.

- Frogley, M. R., Chepstow-Lusty, A., Thiele, G., & Aucca Chutas, C. (2025). Trees, terraces and llamas: Resilient watershed management and sustainable agriculture the Inca way. Ambio, 54(5), 793–807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-024-02121-5

- Kosiba, S. (2018). Cultivating Empire: Inca intensive agricultural strategies. In S. Alconini & A. Covey (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Incas (pp. 227–246). Oxford University Press.

- MDPI Archaeologies. (2023). Spatial, Functional, and Constructive Analysis of the Water Resource at the Archaeological Center of Tipón, Cusco, Peru. https://www.mdpi.com/2571-9408/7/12/307

- Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. (2023). Pre-Hispanic terrace agricultural practices and long-distance transfer of plant taxa in the southern-central Peruvian Andes. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 33, 375–391.