Evidence of human sacrifice in ancient Andean societies dates back to early periods. Researchers find such evidence in human remains, reliefs, textiles, ceramic paintings, and sculptural vessels.

Johan Reinhard

The Term Sacrifice

Sources indicate that the term for sacrifice or offering was capacocha or capac hucha.

María Rostworowski analyzed this term, proposing that capac means “lord” or “sovereign”. Cocha refers to lakes or the sea, based on the practice of washing offerings.

The term capacochas was used for both human sacrifices and sacrificial offerings at the Vilcanota temple. Colonial documents confirm that capacochas referred to these sacrifices, including both the individuals and their remains.

Rostworowski idea was that Andean people did not view human sacrifices as crimes or evils but as acts that ensured a glorious future.

Gerald Taylor, in his version of the Huarochirí document, describes hucha as duty, debt, or obligation. Thus, capac hucha represents the performance of a ritual obligation of utmost importance and splendor.

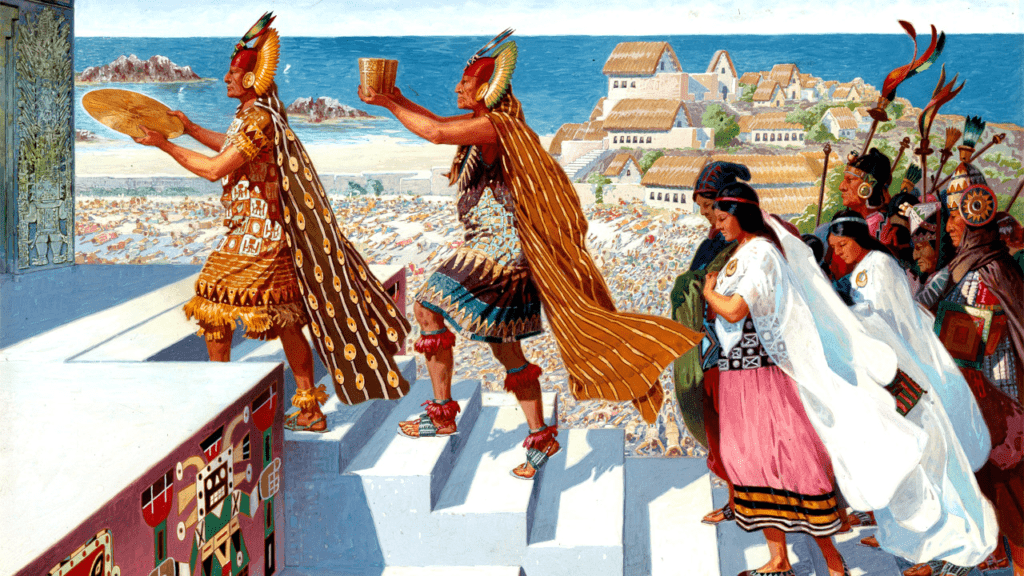

Cieza de León also used capacochas to describe the annual gathering of huacas in Cusco.

The ceremony aimed to demonstrate the huacas‘ effectiveness, ensuring that the Sapa Inca recognized and rewarded them with offerings.

During these gatherings, people sought prophetic answers about events such as the Sapa Inca’s fate.

Deities responded through their priests after offerings of auquénidos, guinea pigs, and birds were made. Accurate prophecies led to rich offerings the following year, while inaccurate ones diminished the deity’s credibility.

Human sacrifice was central to the Inca religion and played a key role in the Inca system of exchange and reciprocity.

It was a means for the centralized power to assert control over conquered populations, who, in turn, showed submission and loyalty to the Sapa Inca.

The sovereign integrated these groups into the redistributive system, providing them access to various products, including divine protection.

Religious Control and Integration

The Inca control over other populations in the religious sphere began with the conquest.

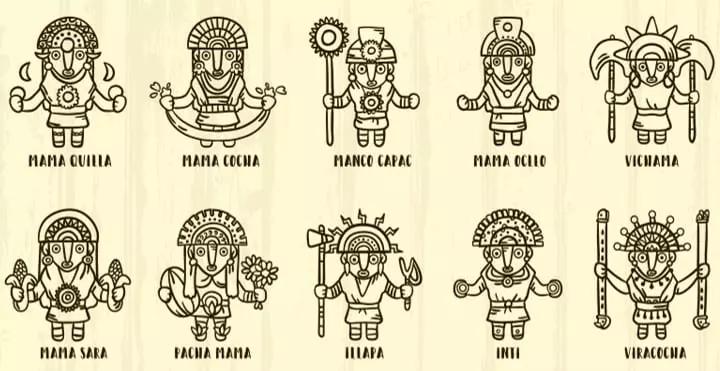

The Inca took the huaca, or sacred entity of the group, to Cusco and kept it “captive” to prevent its protectors from rebelling against their dominators.

They believed that as long as they controlled the protective deity, the group’s strength would diminish.

Thus, the sovereign controlled the specific deities of the conquered peoples and access to the divine.

Some huacas stayed in their regions but were brought to Cusco on certain occasions to participate in ceremonies.

The presence of local huacas in Inca-centric ceremonies also demonstrated the submission, loyalty, and fidelity of the conquered peoples’ gods to the dominant state’s deities.

This religious scheme mirrored the Inca economic and political system, reflecting the reciprocity that involved both fidelity and recognition.

Subjugated groups gained access not only to material goods but also to the blessings of deities controlling natural phenomena, food production, and health.

This access was first reserved for the sovereign, then for central power priests, and finally for local cult ministers

References

- Ávila, Francisco de, Dioses y hombres de Huarochirí, trad. de José María Arguedas, Lima, University Antonio Ruiz de Montoya, 2007.

- Rostworowski, María, “Peregrinaciones y procesiones rituales en los Andes”, Journal de la Société des Américanistes, vol. 89-2, 2003, pp. 97-123.