Before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century, the largest empire in pre-Columbian America rose high in the Andes Mountains—a sacred and political landscape shaped by the vision of the Inca. This vast and deeply spiritual territory was called Tawantinsuyo, a term often translated simply as “Inca Empire,” but whose cosmic meaning goes far beyond mere geography.

What Does Tawantinsuyo Mean?

The word Tawantinsuyo is formed by two Quechua elements:

- Tawa means four

- Suyo means region or province

So Tawantinsuyo means “The Four Regions Together” or “The Fourfold Land.” It describes not only a territorial structure but also a cosmological organization—a mirror of how the Andean people perceived the universe, with balance, duality, and reciprocity at its center (Moseley, 2001).

The Four Suyos: A Sacred Order

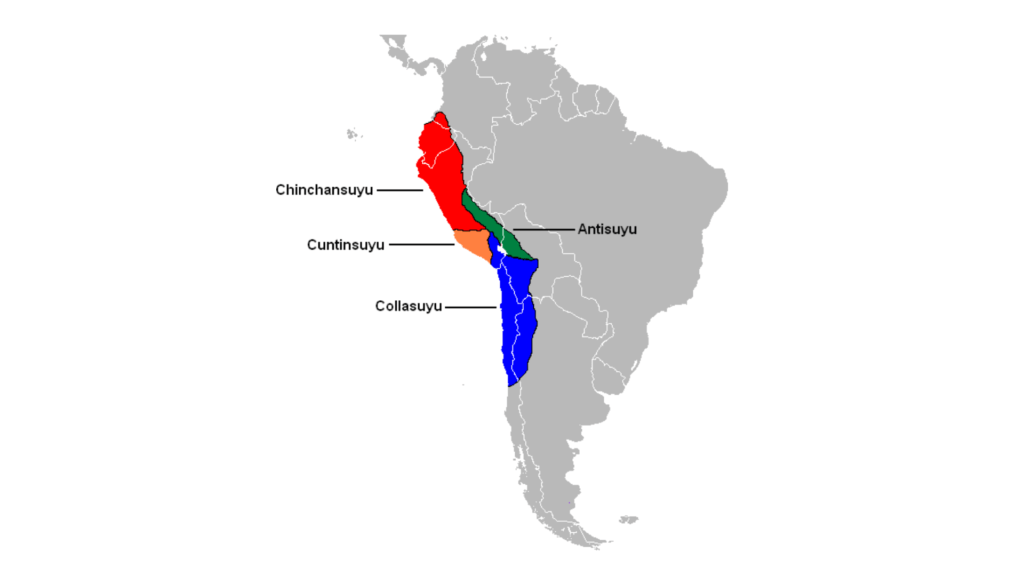

The Inca organized the Tawantinsuyo into four suyos, each radiating from the navel of the world, Qosqo (Cusco), which they considered the center of the Inka universe.

- Chinchaysuyo – Northwest, extending toward present-day Ecuador and the coast. Known for its warrior cultures and tropical goods.

- Antisuyo – East, covering the jungle regions, home to mysterious Amazonian tribes and sacred plants like ayahuasca.

- Collasuyo – South, reaching into present-day Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. A land of high plains (altiplano), herders, and deep ritual traditions.

- Contisuyo – Southwest, the smallest region, linking Cusco to the Pacific Ocean, representing the transition between the Andes and the coast (Rostworowski, 1999).

This quadripartite division mirrored the Andean worldview of duality and complementarity, such as hanan (upper) and hurin (lower), the male and female energies that sustain life.

Qosqo: The Sacred Center

At the spiritual and political heart of the Tawantinsuyo was Qosqo, often written Cusco today. According to myth, this city was founded by Manco Qhapaq and Mama Ocllo, the divine children of the Sun (Inti), who emerged from Lake Titicaca to civilize the world.

Qosqo was laid out in the shape of a puma, a powerful sacred animal, and its major temples and roads aligned with celestial bodies. The Qhapaq Ñan, or Great Inka Road, extended from here to the four suyos, forming a spiritual and administrative network that still shapes the Andean world (Hyslop, 1984).

Not Just an Empire: A Living Organism

Unlike Western empires based on conquest and individual rulers, Tawantinsuyo functioned more like a living body, governed by the principle of Ayni (sacred reciprocity) and collective responsibility.

Land was divided into three parts:

- One for the state,

- One for the gods (wak’as),

- One for the community.

Andean communities carried out work communally through minka and ayni, and they stored resources in state granaries called qullqas to ensure balance in times of hardship. The Inca was not only a political leader, but also the Sapa Inca—the unique son of the Sun, a living bridge between Kay Pacha (this world), Hanan Pacha (the upper world), and Uku Pacha (the inner world) (Murray, 1980).

Spiritual Foundations of Tawantinsuyo

The true power of Tawantinsuyo lay not only in its administration but in its spiritual architecture. Andean builders aligned everything—roads, temples, terraces—with cosmic forces. Rituals honoring Pachamama (Mother Earth), Inti (the Sun), and the Apus (sacred mountains) were central to sustaining harmony.

Ceremonial centers like Saqsaywaman, Pisac, Ollantaytambo, and Machu Picchu were built with astronomical precision, blending human work with divine design. These sites functioned as portals between worlds, reminding us that the Tawantinsuyo was as much a spiritual empire as a political one (Dean, 2010).

Legacy of Tawantinsuyo Today

Though the Inka Empire fell to Spanish conquest in the 1500s, the spirit of Tawantinsuyo lives on in Andean languages, rituals, music, dance, and cosmology. Millions of people across Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Chile, and Argentina still practice forms of Ayni, speak Quechua, and celebrate festivals that blend Inkan and Catholic traditions.

Understanding Tawantinsuyo helps us reconnect with a holistic way of seeing the world, one where land, spirit, and community are not separate but united in sacred harmony.

Bibliography

- Dean, C. (2010). A Culture of Stone: Inka Perspectives on Rock. Duke University Press.

- Hyslop, J. (1984). The Inka Road System. Academic Press.

- Moseley, M. (2001). The Incas and Their Ancestors: The Archaeology of Peru. Thames & Hudson.

- Murra, J. (1980). The Economic Organization of the Inka State. JAI Press.

- Rostworowski, M. (1999). History of the Inca Realm. Cambridge University Press.

- Zuidema, R. T. (1982). Inka Civilization in Cuzco. University of Texas Press.