Among the many traditional dishes of Peru, few are as rich in symbolism and history as Chiriuchu. This festive plate is more than just a combination of flavors—it is a ritual of identity, a culinary offering that bridges the Andean and Catholic worlds.

It is most commonly associated with the celebration of Corpus Christi in Cusco, a city once at the heart of the Tawantinsuyu, the Inca Empire.

What is Chiriuchu?

The word Chiriuchu comes from Quechua:

- “Chiri” means cold,

- “Uchu” means chili or spicy stew.

So, Chiriuchu literally translates to “cold chili” or “cold spicy dish”, although it’s more accurately understood as a cold ceremonial meal composed of various local ingredients, each with cosmological and cultural meaning.

This traditional dish is served cold, not just for practical reasons during large processions, but because coldness is linked to ceremonial purity in Andean cosmology. Coldness is also a sign of offering, similar to how foods were once left on altars for Apus (sacred mountains) and Pachamama (Mother Earth) (Flores Ochoa, 2005).

Ingredients: A Symbolic Landscape

Chiriuchu is not one dish but a plate composed of many. The ingredients reflect the diversity of the Andes and the sacred geography of Peru:

- Roasted guinea pig (cuy): A sacred animal in Inca rituals, representing abundance.

- Chicken: A colonial addition, symbolizing the mestizaje or blend between Indigenous and Spanish cultures.

- Charqui (dried alpaca or llama meat): Evokes ancient preservation techniques and the highlands’ legacy.

- Corn tortillas (t’anta wawa or torrejas de maíz): Associated with ceremonial bread offerings.

- Sausage: Introduced during colonial times, showing the fusion of Spanish flavors.

- Cheese and seaweed: Represent coastal connections, especially important in Andean cosmology, where Mama Cocha (Mother Ocean) is a divine force.

- Rocoto (a spicy pepper): Symbol of heat and passion, balanced by the coldness of the dish.

- Huevos de pescado (fish roe): Rare and valuable, possibly linked to fertility and water spirits.

Each element represents one of the three worlds in Andean belief:

- Hanaq Pacha (the upper world),

- Kay Pacha (the world of the living),

- Uku Pacha (the inner world or underworld) (Zuidema, 1977).

Chiriuchu and Corpus Christi

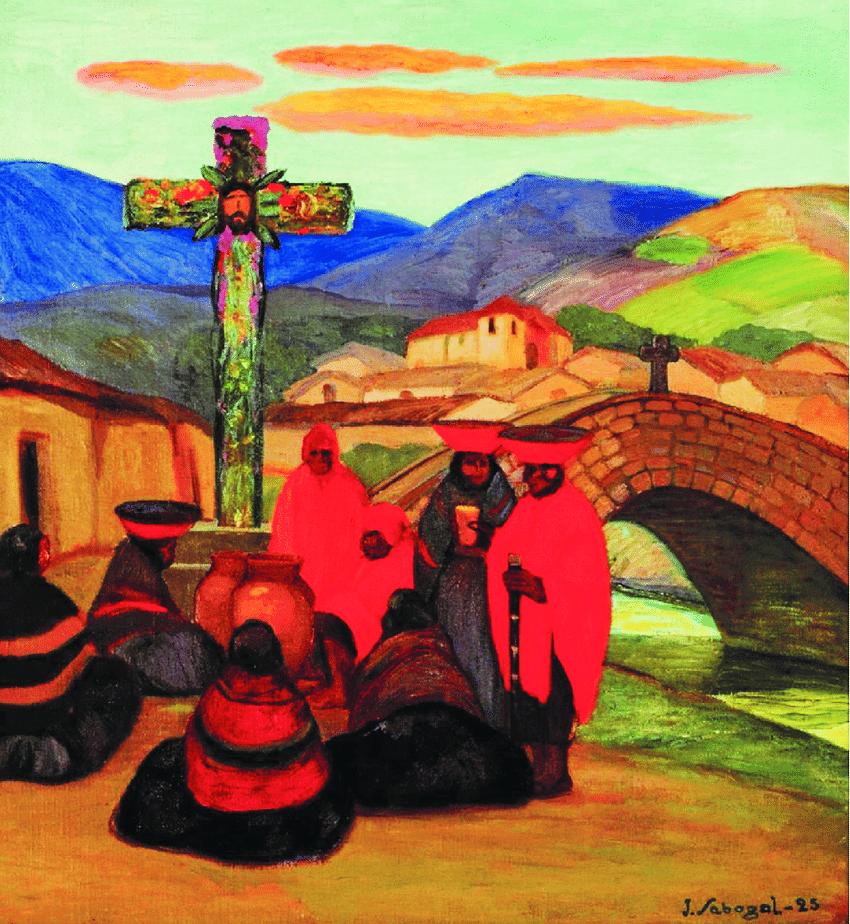

Chiriuchu is traditionally prepared for Corpus Christi, a Catholic feast that in Cusco has uniquely merged with Incan religious festivities. During this celebration, statues of saints and virgins are paraded through the streets, accompanied by dances, music, and food.

But beneath the Catholic layer lies the memory of Inti Raymi, the ancient solstice festival that honored the Sun (Inti).

Many scholars agree that Corpus Christi replaced or merged with this native festival to ease the religious transition imposed during colonization (Dean, 2010). In this sense, Chiriuchu is not just food—it is a syncretic offering to both the Christian saints and the Incan deities.

A Culinary Expression of Ayni

At its core, Chiriuchu is a reflection of Ayni, the Andean principle of reciprocity. Sharing this meal during Corpus Christi is an act of community, balance, and gratitude. Each family contributes a part, echoing the ancient communal feasts known as minka or ayllu gatherings.

Preparing and eating Chiriuchu is a way of honoring ancestors, the land, and the living connection between past and present. It is food, but also prayer, ritual, and identity.

To taste Chiriuchu is to taste the Andes. It is a dish where history, geography, and spirituality meet on one plate—offered cold, but rich with the warmth of tradition.

Whether you’re a visitor to Cusco or a local returning to your roots, this ceremonial food invites you to reflect on what it means to belong, to share, and to remember.

Bibliography

- Dean, C. (2010). A Culture of Stone: Inka Perspectives on Rock. Duke University Press.

- Flores Ochoa, J. (2005). Los rituales del mundo andino. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- Zuidema, R. T. (1977). The Inca Calendar. In Native South Americans (J. Steward, ed.). University of Texas Press.

- Matos Mar, R. (2002). El mundo ceremonial andino. Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú.

- Laime Ajacopa, M. (2007). Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk’ancha (Quechua-Español). Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.