In the previous blog, we explored how Inca agriculture was a sacred dialogue with Pachamama and the living energy of Kawsay. Today, we turn our gaze to the sky — to the cosmic cycles and ritual calendars that guided every seed, harvest, and ceremony. For the Andean peoples, time was not linear but Pacha — a living fabric woven by the movements of Inti, Killa, and the stars. To follow these celestial rhythms was to live in harmony with the pulse of the universe itself.

Ritual Calendars and Cosmic Cycles for Agriculture

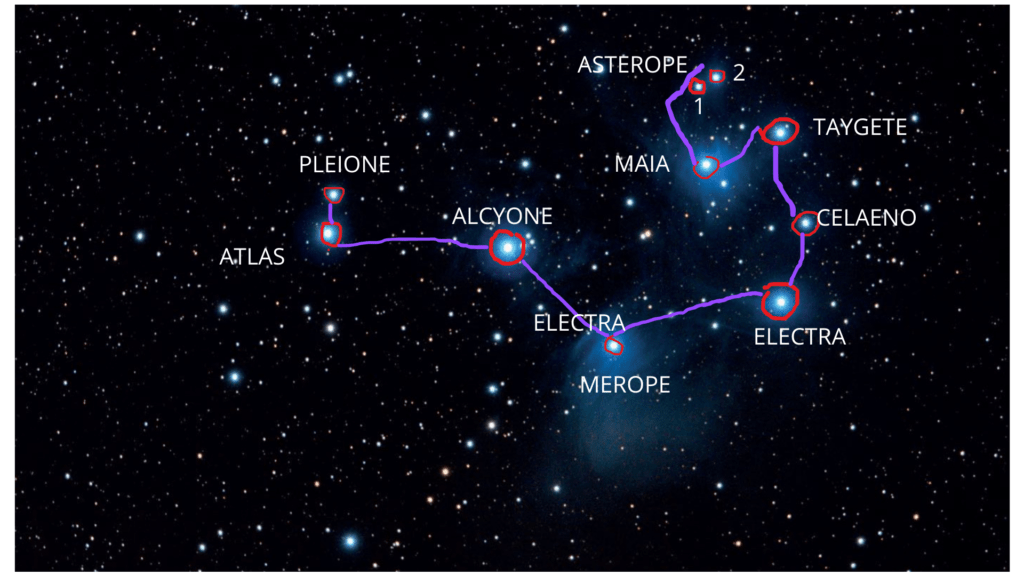

The Inca calendar was both astronomical and spiritual—a woven system of time that linked agricultural work to the rhythm of the stars. The Incas aligned sowing, harvesting, and ritual ceremonies with the solar and lunar cycles. They observed the movement of constellations such as the Chakana (Southern Cross) and Pleiades, known as Qollqa, the celestial storehouse.

Each agricultural phase mirrored a cosmic event. The Inti Raymi marked the rebirth of the solar cycle, a time to thank Inti for the returning light. The Coya Raymi (September equinox) honored the feminine aspect of the cosmos and initiated planting season with rituals to Pachamama. During Capac Raymi (December solstice), communities offered gratitude for the ripening crops, celebrating balance between light and shadow.

Through this calendar, agriculture became an act of cosmic synchronization. Every ritual ensured that human action resonated with the heartbeat of the universe—Pachakuti, the sacred cycle of renewal and transformation. To cultivate was not only to feed the body but to maintain harmony between Kay Pacha, Hanan Pacha, and Uku Pacha.

Agriculture: Seeds of Reciprocity and Biodiversity

In the Andean valleys, agriculture was also an act of communal ayni. Farmers exchanged seeds across ecological zones—from the highlands to the jungle—expanding biodiversity and resilience in times of drought or frost (Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 2023). These exchanges were not economic but ceremonial, reinforcing ties of kinship between human communities and the landscape itself.

According to Kosiba (2018), the Inca state institutionalized these principles at an imperial level, creating vast agricultural networks that maintained balance between productivity and sacred reciprocity. Fields were divided between the Sun, the state, and the people—reflecting a cosmological order where no act of cultivation was separate from the divine.

The Temple of the Living Earth

Each chakra (field) was considered a microcosm of the universe, tended with ritual offerings of coca, chicha, and song.

Before planting, farmers performed pachamamaq challay, the ceremonial feeding of the earth, to ensure that the seeds would awaken in harmony. These gestures were not superstition—they were a recognition that life depends on relationship, not domination.

Modern ecological science now echoes what the Incas knew intuitively: the health of an ecosystem depends on reciprocity, diversity, and respect for cycles.

In this sense, Inca agriculture offers not only a historical model but a spiritual ecology—a way of remembering that the Earth is alive and that all cultivation is communion.

References

- Bray, T. L. (2017). Water, Ritual, and Power in the Inca Empire.Latin American Antiquity. Cambridge University Press.

- Frogley, M. R., Chepstow-Lusty, A., Thiele, G., & Aucca Chutas, C. (2025). Trees, terraces and llamas: Resilient watershed management and sustainable agriculture the Inca way. Ambio, 54(5), 793–807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-024-02121-5

- Kosiba, S. (2018). Cultivating Empire: Inca intensive agricultural strategies. In S. Alconini & A. Covey (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Incas (pp. 227–246). Oxford University Press.

- MDPI Archaeologies. (2023). Spatial, Functional, and Constructive Analysis of the Water Resource at the Archaeological Center of Tipón, Cusco, Peru.https://www.mdpi.com/2571-9408/7/12/307

- Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. (2023). Pre-Hispanic terrace agricultural practices and long-distance transfer of plant taxa in the southern-central Peruvian Andes. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 33, 375–391.